(This post is part of the algebra notes series.)

Finite groups and subgroups - part 2

These notes are based on the book Contemporary Abstract Algebra 7th ed.

More subgroup tests

Two-Step subgroup test

Let G be a grop and let H be a nonempty subset of G. If ab ∈ H whenever a,b ∈ H(H is closed under the operation), and a-1 ∈ H whenever a ∈ H, H is a subgroup of G.

Proof: Let a,b ∈ H. Since H is non-empty by our hypothesis, if we can show that ab-1 ∈ H, then by the one-step subgroup test H≤G. Since b ∈ H, b-1 ∈ H by our hypothesis. Since a,b-1 ∈ H , and since H is closed by our hypothesis, we can conclude ab-1 is in H.

Showing a subset is not a subgroup

So far, we've gone over two ways to prove if a subset H is a subgroup. But how can we show that a subset is definitely not a subgroup? Here's a few ways

- Show e ∉ H

- Show that there exists an a∈H with a-1∉H.

- Show that there exists some a,b∈H with ab∉H.

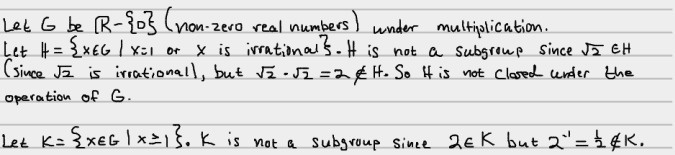

Example of showing a subset is not a group

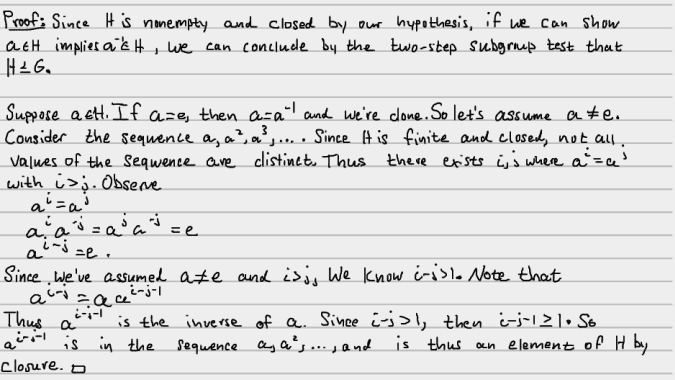

Finite Subgroup test

Let H be a nonempty finite subset of group G. If H is closed under G's operation, then H is a subgroup of G.

Examples of Subgroups

Defining <a>

<a>= {an | n∈Z} = {a-1,a0,a1,a2, ...}. a0 is defined to be the identity.

<a> is called the "cyclic subgroup generated by a".

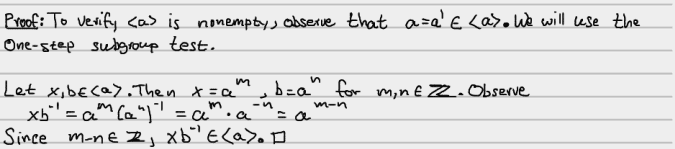

<a> is a subgroup.

Let G be a group and let

abe any element of G. Then<a>is a subgroup of G.

Note that xb-1 was used over the conventional ab-1 since

we wanted to avoid confusion between the element a and the set <a>.

A note on proof strategy

Similar to the subgroup test proofs in part 1, whenever we perform the one-step subgroup test and have declared a and b in the subgroup, it's easier to just start with ab-1 and verify that it has the properties necessary to be in the subset. It can be verify difficult to start by taking the values of a and b and manipulating them to appear in the same form as ab-1, so it's better to start with ab-1 and simply verify that it has the needed properties.

Cyclic groups

In the event that <a>=G for some a∈G, G is called "cyclic" and a is

called a "generator" of G. Just because <a> is infinitely long does not mean

the set produced by it is infinitely long since sets do not have duplicate

elements.

Every cyclic group is abelian. This is because every element in <a> is in

the form an for some integer n. So if we were to pick two elements

out of <a>, say ai and aj, performing the group

operation on them yields

aiaj=ai+j=aj+i=ajai.

Center of a group

The center of a group, Z(G), is the set of elements of G that commute with all elements of G. Notationally,

Z(G)={a∈G | ax=xa ∀x∈G}.

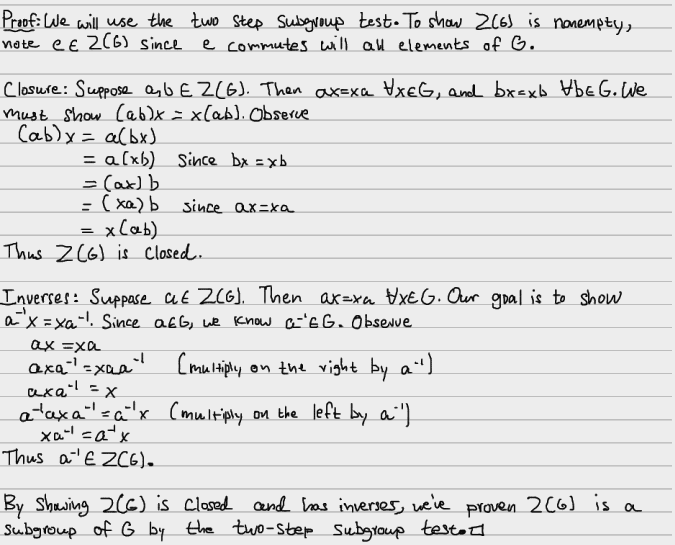

The center is a subgroup

The center of a group G is a subgroup of G.

Centralizer of a in G

Let a be a fixed element of a group G. The centralizer of a in G, C(a), is the set of all elements that commute with a. Notationally,

C(a) = {g∈G | ga=ag}.

Distinguishing the center and a centralizer

It can be a little difficult to keep the terms "center" and "centralizer" straight, especially since they sound the same and have similar definitions. Do your best to remember that the center is associated with an entire group, while the centralizer is associated with a single element in a group. Additionally, if an element is in C(a) for any a∈G, it's guaranteed to be in Z(G). Think about why :)