(This post is part of the programming languages 4th edition series.)

Programming Language Translation Issues

These notes are based on Programming Languages: Design and Implementation.

Section 3.1: Programming Language Syntax

define syntax:

the arrangement of words as elements in a sentence to show their relationship

In programming terms, syntax describes the sequence of symbols that make up valid programs.

- Syntax alone is not sufficient for preventing ambiguity

x=2.45 + 3.67can mean different things based upon the type of x and whether+is integer addition or real addition

define semantics:

Non-syntax attributes of a programming language. Includes declarations, operations, sequence control, etc

Section 3.1.1: General syntactic criteria

Readability

- A program is readable if data/algorithm is apparent by inspection of program text

- A readable program is said to be self-documenting

- The following features enhance program readability:

- natural statement formats

- structured statements

- liberal use of keywords and noise words

- embedded comments

- unrestricted length identifiers

- mnemonic operator symbols

- free-field formats

- complete data declarations

- Readability of a program is not guaranteed by language design

- Bad programmers make unreadable code, no matter the language!

- Bad syntax design can make it very hard for good programmers to write

readable code

- APL

-

COBOL was designed to emphasize readability

- writing and translation at the expense

-

It is good when syntactic differences reflect semantic differences

- Program constructs that do similar things should look similar

- Program constructs that do different things should look different

- Languages that provide only a few syntactic constructs lead to less readable

programs

- APL

- SNOBOL4

- Some syntax errors may alter the meaning of a statement without being

syntactically incorrect.

- Mismatching parentheses in LISP

Writability

- Syntax features that make programs easy to write usually make them hard to

read

- Writability enhanced by concise and few syntax structures

- Readability enhanced by verbose and varied syntax structures

- Implicit syntax (allowing declarations/operations to be unspecified) make programs shorter and easier to write but harder to read.

- A syntax is redundant if it can say the same thing in more than one way

- Sometimes this is useful

- Sometimes this makes programs harder to write

- Languages that have no redundancy are often difficult to use

Ease of verifiability

- Program correctness

- Also known as program verification

- Understanding programming statements is easy, but producing correct programs is hard.

- Some programs can be mathematically proven correct

- This will be discussed later

Ease of translation

- Another goal is making programs easy to translate into executable form

- Readability/writability directed at programmer needs, ease of translation

directed at the program translator.

- Lisp is not very readable or writable but is very easy to translate

- COBOL is hard to translate due to number of statement forms allowed

Lack of ambiguity

- Ambiguity is a central problem in every language design

- A language ideally provides a unique meaning for every syntax construct

- Problems of ambiguity usually arise in interplay between different structures

Section 3.1.2: Syntactic elements of a language

Character set

- Character set choice one of the first choices to be made in syntax design

- Due to various written languages, 16-bit representations must be considered

Identifiers

- widely accepted syntax:string of letters and digits that start with a letter

- Variations between languages include

- inclusion of special characters (such as . and _)

- length restrictions

Operator symbols

- Most languages use + and - to represent the two basic arithmetic operations

Keywords and reserved words

define keyword:

an identifier used as a fixed part of the syntax of a statement ("if" beginning a conditional or "for" beginning an iteration)

define reserved word:

a keyword that may not be used as a programmer-chosen identifier

- Most languages used reserved words

- Most languages begin with a keyword designating the statement type

- IF

- WHILE

- FORTRAN is difficult due to "DO" or "IF" may not necessarily indicate

iteration or conditional statement

- DO and IF are not reserved words. They can be variable names.

- Addition of a new reserved word to a program can break previous programs that used the new word as a variable name.

Noise words

define noise word:

Noise words are optional words that are inserted into statements to improve readability.

- Example: COBOL "GO TO"

- GO required, TO optional

Comments

- Comments are important part of program documentation

- Several comment types

- Separate comment lines

- Delimited by special markers (/ / in C)

- Beginning anywhere and terminated by end of line (// in C++)

Blanks (spaces)

- Rules on use of blanks vary between languages

- In C, blanks are not significant except in string literals

- Some languages use blanks as separators, so they are important

- SNOBOL4, concatenation represented by a blank

Delimiters and brackets

define delimiter:

A syntax element used to mark the beginning or end of some syntax unit such as a statement or expression.

- Brackets are paired delimiters

- parenthesis

- begin...end pairs

- Usually serve the purpose of removing ambiguities by defining explicit boundaries

Free and fixed-field formats

define free-field:

A syntax is free-field if program statements may be wr itten anywhere on an input line without regard for positioning on the line.

define fixed-field:

A syntax is fix field if the positioning on an input line conveys information.

- Fixed field syntaxes are a remnant of the punch-card era

- Fixed-field syntax is increasingly rare today

- free field is the norm

Expressions

define expression:

An expression is a function that accesses data objects in a program and returns some value

- The basic syntactic building block from which statements are built

- In imperative languages, expressions form the operations that allow for the machine state to be changed by each statement.

- In applicative(functional) languages, expressions form the basic sequence control that drives execution.

Statements

- The most prominent syntactic component in imperative languages

- Statement syntax has critical effect on

- regularity

- readability

- writability

- Most programming language provide different syntax structures for different statement types

- Different types of statements:

- A simple statement contains no other statements

- A structured(AKA nested) statement may contain embedded statements

Section 3.1.3: Overall program-subprogram structure

Separate subprogram definitions

- C has each subprogram definition treated as a separate syntax unit

- Each program compiled separately

- Compiled programs linked at load time

- Object orientation requires information to be passed among the separately

compiled units

- Inheritance requires the compiler to process some of the subprogram issues

Separate data definitions

- Group together all operations that manipulate a data object

- Subprogram may consist of all operations that create/print data object

- The general approach of the class mechanism if Java, C++, Smalltalk

Nested subprogram definitions

- Important for building modular programs during period of ALGOL, FORTRAN, and Pascal.

- In Pascal, subprogram definitions appeared within main

- May contain other subprograms nested within their definitions

- This type of subprogram allows for static type checking

Separate interface definitions

- FORTRAN permits easy compilation of subprograms, but data used across

subprograms may have different definitions

- compiler will not be able to detect this at compile time

- Pascal allows compiler to have access to all these definitions to aid in

finding errors

- However, the entire program must be recompiled at the slightest change

- C, ML, and Ada use aspects of both techniques to improve compilation

define implementation:

a program implementations consists of several subprograms that are intended to interact together. The components, called modules, are linked together to create an executable, but only any changed components need to be recompiled.

- With implementations, data passed among procedures of a component must have

common declarations like in Pascal.

- Leads to efficient compiler checking

- To pass information between too separately compiled components, additional

data is needed.

- C header files form the specification component, .c files the "implementation component"

Data descriptions separated from executable statements

- COBOL contains early form of component structure

- Data declarations/statements divided into data and procedure "divisions"

- The environment division consists of declarations involving the external operating environment.

Unseparated subprogram definitions

- SNOBOL4 represents extreme in program organization

- No syntactic distinction made between main program and subprogram statements

- In SNOBOL4, statements simply execute

- Where subprograms begin and end are not different in syntax

- Execution of a function starts a new subprogram

- RETURN function ends a subprogram

- Very chaotic! Only useful in allowing run-time translation

Section 3.2: Stages in translation

- Translation of a program from syntax to executable is central in every implementation

- Translation can be simple

- Perl

- Prolog

- Lisp

- Translation is usually complex

- Translation is trivial if you're willing to accept slow execution speed

- Execution speed is a big deal, that's why we go through the effort of translating programs into efficient executables

Translation can be divided into two major parts: analysis of the source and synthesis of the executable program object. These processes alternate, often on a statement-by-statement basis.

Translators can be grouped by the number of passes they make over the source:

- Simple compiler usually uses two passes

- First analysis pass decomposes program. Gets info from program

- Second pass typically generates an object from the collected information

- If compilation speed is important, one pass may be used

- As program is analyzed, it is instantly converted to object code

- If execution speed is important, a three-or-more pass compiler may be used

- First pass analyzes source program

- Second pass rewrites the source program into a more efficient form via well defined optimizations

- The third pass generates the object code

- The relationship between number of passes and compiler speed is no longer a

big factor.

- The big factor now is language complexity

Section 3.2.1: Analysis of the source program

To a translator, the source appears at first as one long sequence of symbols. The subprograms, statements, etc, visible to the programmer are not apparent to the translator yet.

Lexical analysis (scanning)

- The initial phase of any translation is to group the sequence of characters

into its parts:

- identifiers

- delimiters

- operator symbols

- numbers

- keywords

- etc

- This phase is called lexical analysis, and the program units produced are called lexical items or tokens.

- Individual lexical items are called lexemes

- Lexical items convey a single meaning

The lexical analyzer (scanner) reads lines of the input source, breaks down the lines into lexemes, and passes the lexemes to the later stages of the translator.

The lexical analyzer must:

- identify the type of each lexeme

- number

- identifier

- delimiter

- etc

- attach a type tag to the lexeme

- convert items to internal representations

Lexical analysis usually requires a majority of translation time.

Syntactic analysis (parsing)

- The second stage of translation

- Larger program structures are identified using lexical items

- statements

- declarations

- expressions

- etc

Syntactic analysis usually alternates with semantic analysis

- Syntactic analyzer groups a sequence of tokens into a syntactic unit such as

- statement

- expression

- declaration

- Semantic analyzer processes this unit.

- Syntactic and semantic analyzers communicate via stack

Semantic analysis

- The central phase of translation

- Syntactic structures recognized by the syntactic analyzer are processed

- The bridge between analysis and synthesis stages of translation

- Many subsidiary functions occur in this stage

- symbol-table maintenance

- most error detection

- expansion of macros

- execution of compile-time statements

- The output is usually some internal form of the final executable

- This executable is then manipulated by the optimization stage

- The semantic analyzer is usually split into a set of smaller semantic

analyzers.

- Each small semantic analyzer will handle a particular type of program construct.

- These small analyzers interact with each other, usually through the central symbol table.

The functions of the semantic analyzers depend on the programming language and the organization of the translator. The most common functions are:

Symbol-table maintenance

define symbol table:

One of the central data structures in every translator. It contains an entry for each different identifier encountered in the source program.

- The lexical analyzer makes the initial entries

- The symbol-table entry contains more than just the identifier:

- type (simple variable, array name, parameter, etc)

- type of value (integer, float)

- referencing environment

- Semantic analyzers enter information into the table as they process:

- declarations

- subprogram headers

- program statements

- Other parts of the translator use this information to make efficient code

The symbol table for compiled languages is usually discarded at the end of translation.

- It may be retained

- Useful for debugging

- Used by languages that allow new identifiers to be created at run-time

Insertion of implicit information

- Information implicit within the source must be made explicit in the lower

level object program.

- Type guessing

- FORTRAN: var used without declaration can be type guessed based on first letter

Error detection

- Syntactic and semantic analyzers must be able to handle incorrect programs.

- The lexical analyzer may send the syntactic analyzer a token that does not fit its surrounding context

- The semantic analyzer must recognize errors, produce an error message, and continue syntactic analysis of the rest of the program.

Macro processing and compile-time operations

-

Not all languages include macro features.

- For languages that do, they are generally handled in semantic analysis

-

A macro is a piece of program text that has been separately defined that will be inserted into the program during translation when the macro call is encountered

- Like a subprogram, except the macro body is substituted for each call during translation

- Sometimes macros are just simple strings, like the constant PI to be 3.14

- Sometimes they look like subprograms with parameters

-

Semantic analyzers must identify the macro call and perform the substitution

- This usually involves interrupting lexical and syntactic analyzers and directing them to work on the macro body.

- If the macro body is already partially translated, the semantic analyzer can process it directly, inserting the object code and making symbol table entries.

-

A compile-time operation is an operation intended to be performed during translation with the purpose of controlling the translation of the source

- C "#define" lets constants/expressions be evaluated before compilation

- C "#ifdef" (if defined) allows for different code to be compiled based on the presence/absence of certain variables

An example C source file that can compile to alternate versions

# define pc /* Set to pc or unix */ ... DoStuff() #ifdef pc /* do pc version */ #else /* do unix version */ #endif

Section 3.2.2: Synthesis of the object program

The final translation stages deal with constructing the executable program from the "internal executable" produced by the semantic analyzer. Code generation and optimization will occur here. If subprograms are translated separately, or if libraries are used, linking and loading will be needed to produce the executable.

Optimization

- Code generators generate object code from the semantic analyzer's produced intermediate code.

- Before generation, optimization of the intermediate code occurs.

- The semantic analyzer usually does not worry about surrounding code

- This means the initial intermediate code can be very inefficient

Example: The statement A=B+C+D

The semantic analyzer may generate the following intermediate code

Temp1 = B+C Temp2 = Temp1 + D A = Temp2

The code generators may generate the following inefficient code

load register with B add C to register store register in Temp1 load register with Temp1 add D to register store register in Temp2 load register with Temp2 store register in A

The register storage and loading is redundant since all data can be kept in the register before storing the result in A.

Let the semantic analyzers produce poor code, and clean it up during optimization.

Code generation

- After intermediate code has been optimized, it must be formed into one of

- assembly language

- machine code

- other object form

- Code generation involves formatting the output from the information contained in the internal program representation (intermediate code)

- Output code may be directly executable, or may require linking/loading

Linking and loading

- The final stage of translation

- Output code from separate subprogram translations are placed into final executable

- Up until this point, executable programs are in almost final form

- except where the programs reference external data or subprograms

- The incomplete locations are specified in loader tables created by the translator

- The linking loader uses the loader tables to link separate translation code together.

- The result is the final executable, ready to be run

Bootstrapping

- Often the translator for a new language is written in that language

- Initial Pascal compiler was written in Pascal

- How does this process get started?

- How does the first compiler get compiled?

- The process is called bootstrapping

- One way to bootstrap is to write the compiler by hand

- The process is tedious but not difficult

- Now the hand translated compiler can be executed

- A compiler written in the language itself can now be made using this hand translated compiler

Diagnostic compilers

- Rapid turnaround and compilation time were the major goals

- Student programs did not execute very long

- Student programs were discarded after being executed correctly

Section 3.3: Formal translation models

define grammar:

The formal definition of the syntax of a programming language

- grammar consists of a set of rules (called productions)

- the rules specify the sequence of characters (lexical items) that form allowable programs in the language being defined.

A formal grammar is just a grammar specified using strictly defined notation.

- The two classes of useful grammars in compiler technology:

- The BNF grammar (context-free grammar)

- regular grammar

Section 3.3.1: BNF Grammars

A simple English sentence is often of the form subject / verb / object.

Example sentences:

The cat/ran/homeThe monster/scared/me

You can break down the examples above further as article / noun / verb /

object.

There are many other types of sentences. An interrogative (question) sentence

may look like auxiliary verb / subject / predicate such as

Did/the cat/run home?Is/the monster/scaring you?

So with a very simple persecutive, we could say a sentence may be a declarative sentence or a question. Notationally, we would say

<sentence> ::= <declarative> | <interrogative>

The symbols ::= stands for "is defined as" and the | symbol stands for "or"

We can then further define <declarative> and <interrogative>:

<declarative> ::= <subject> <verb> <object> <subject> ::= <article> <noun> <interrogative> ::= <auxiliary verb> <subject> <predicate>?

This notation is called BNF, Backus-Naur form. For our purposes, you can consider BNF grammar and Context-free grammar as equivalent terms.

Syntax

- A BNF grammar is composed of a finite set of BNF grammar rules

- These rules define a language - in our case a programming language

- Syntax is only concerned with form, not meaning.

- A programming language consists of a set of syntactically correct programs

- These programs are a sequence of characters

- A syntactically correct program may not make any sense semantically

For example, The home / ran / girl fits the syntax of a simple declarative

sentence, but it doesn't make any sense.

-

The only restrictions an what we call a language:

- Each string must be of finite length

- Each string must contain characters from some fixed alphabet of symbols

-

Examples of languages

- The set of all C assignment statements

- The set of all C programs

- The set of sequences of a's and b's where all a's precede the b's

- ab

- aab

- abb

- Using English to convey language definitions can make things confusing and unclear.

- We solve the problem by using a formal set of rules for determining exactly what strings are in the language.

- In the simple case, a grammar may list the elements of a finite language

For example,

<digit> ::= 0|1|2|3|4|5|6|7|8|9

- The "digit" term is called a syntactic category or a nonterminal.

- It's the name of the language defined by the grammar rule.

-

The symbols making up the strings of the language are called terminal symbols

-

Sometimes an arrow is used instead of

::=.<X> ::= <B>|<C>can be written as X → B|C

Once we've defined a basic set of nonterminals, we can use them to construct more complex strings. Consider the following rule that defines the language of conditional statements

- "Boolean expression and "statement" are syntactic categories (non-terminals)

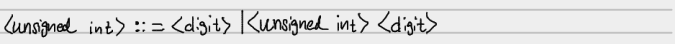

Syntactic categories as they are defined may refer to themselves in the rule. Such a rule is called a recursive rule. For example,

-

This rule defines an "unsigned int" as a sequence of digits.

- The first option is a single digit

- The second option allows another digit to be added on to the initial digit, and so on.

-

A complete BNF grammar is a set of grammar rules

- Together, the rules define a hierarchy of sub-languages

- This hierarchy leads to the top-level syntactic category

- For a programming language, this top-level is usually called

<program>

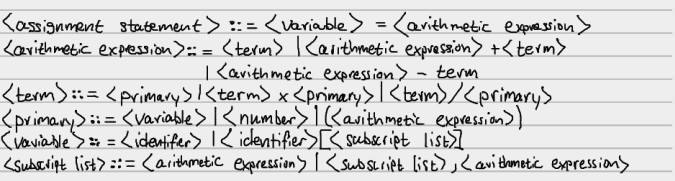

Here's an example of a grammar defining an assignment statement, supposing the

nonterminals <identifier> and <number> are already defined:

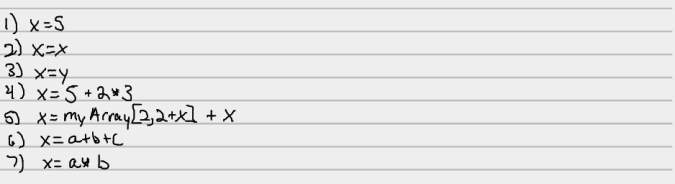

Here are some example strings in the language

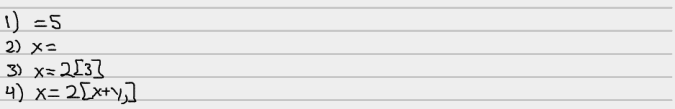

And here are some example strings NOT in the language

Parse Trees

If we're given a grammar, we can use a single-replacement rule to generate strings in the language. For example, the following grammar generates all sequences of balanced parenthesis:

S → SS | (S) | ()

Starting with just S, how can we generate the string "(()())"?

- S → (S), yielding (S)

- Since S → SS, we can substitute into (S) to get (SS)

- Since S → (), we can substitute into (SS) to get (()S)

- Since S → (), we can substitute into (()S) to get (()())

We can show this in a more concise manner, using the symbol ⇒ to indicate that one string is derived from another string.

S ⇒ (S) ⇒ (SS) ⇒ (()S) ⇒ (()())

- Each term in the derivation is called a sentential form.

-

We formally define a language as the set of sentential forms consisting entirely of terminal symbols.

-

To determine if a string is a valid program in the language defined by a BNF grammar

- Use the grammar rules to parse the string

- If the string can be parsed, it is in the language

- If there is no way of parsing the string with the rules, it is not in the language.

- Parse trees result from syntactic analysis

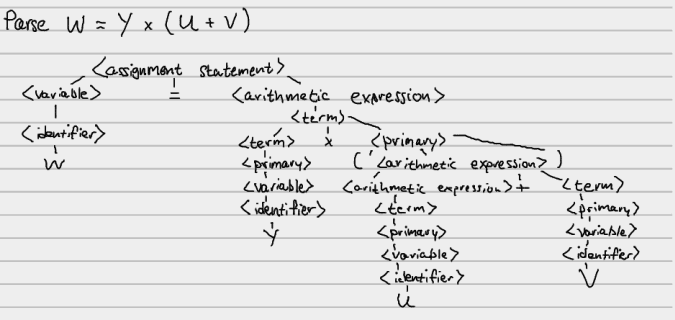

To see if W=Yx(U+V) is in the language of assignment statements defined

earlier, we attempt to construct a parse tree:

- The BNF grammar rules cause the parse tree to in fact be a tree.

- The leaf is a single character / lexical item in the input string

- The intermediate branches are syntactic categories to which the subtree below it belongs.

The same language may be defined by many different grammars.

- BNF grammars cannot define areas involving contextual dependence:

- Preventing multiple definitions of the same identifier

- Preventing a 2d array from being referenced with 3 subscripts

Ambiguity

Avoiding ambiguity is an important problem with syntax. Consider the sentence "They are flying planes". This sentence can be represented in a couple of ways:

They/are/flying planesThey/are flying/planes

These statements can mean different things although they come from the same string.

- Ambiguity is often a property of a grammar

- NOT of a language

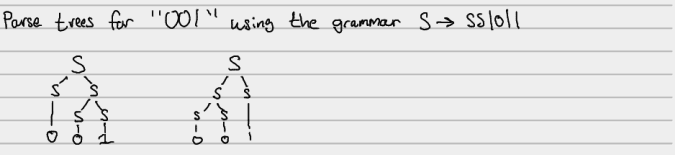

Consider a grammar G, which generates all binary strings:

G: S → SS | 0 | 1

The grammar G is ambiguous. How do we know? We can construct two distinct parse trees for the string "001"

If every grammar for a language is ambiguous, the language is called inherently ambiguous.

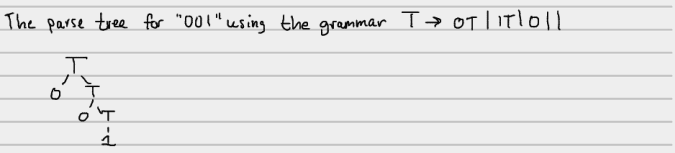

The language of all binary strings is not inherently ambiguous, though. The following grammar generates binary strings unambiguously

G2: T → OT | 1T | 0 | 1

And here's the parse tree for the string "001"

Extensions to BNF Notation

- BNF grammars are not ideal for explaining the rules of a language syntax for

programmers.

- The BNF rule simplicity forces unnatural representation for

- optional elements

- alternative elements

- repeated elements

- Simple syntactic constructs become complex to notate

- The BNF rule simplicity forces unnatural representation for

For example, defining the language of signed integers: digits preceded by a + or - sign

<signed integer> ::= +<integer> | -<integer> <integer> ::= <digit> | <integer><digit>

Extensions to BNF simplify this issue.

Extended BNF notation

These extensions do not alter the power of BNF in anyway, they just make the description of the languages easier

- Optional elements can be enclosed is square brackets []

- Alternative elements can be distinguished with the | symbol

- An arbitrary sequence of element instances can be specified with {...}*

- The sequence can be empty

An example using this extended BNF notation:

<identifier> ::= <letter>{<letter>|<digit>}*

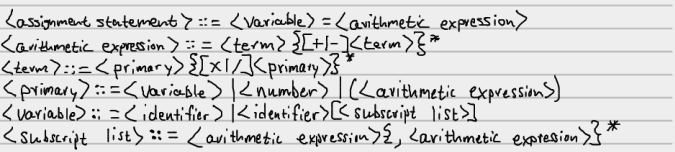

As another example, consider our assignment statement BNF, rewritten to use extended BNF notation

Section 3.3.2: Finite-State Automata

- Lexical analysis breaks source into a stream of tokens

- A state machine can recognize tokens such as

- Identifiers

- Digits

- An if statement

An example Finite-State Automata (FSA) that recognized an odd number of 1s

- Denote the starting state with an arrow that does not come from another state

- The final state is indicated with a double circle

Example application of the FSA above:

| Input | Ending state | Accept the string? |

|---|---|---|

| null | A | no |

| 100 | B | yes |

| 10010 | A | no |

| 100101 | B | yes |

Characteristics of an FSA

- Has a starting state

- One or more final states

- A set of transitions (labeled arcs) from one state to another

- Any string that takes the machine from the initial to the final state is "accepted" by the machine.

Section 3.4: Recursive descent parsing

- We can rewrite extended BNF rules as procedures

Consider the rule for arithmetic expressions discussed earlier:

<arithmetic expression> ::= <term> {[+|-]<term>}*

If we assume that

- The variable

nextcharalways contains the first character of the respective nonterminal getchar()reads in a character

Then we can rewrite the BNF grammar as the following recursive procedure:

procedure Expression;

begin

Term; /* Call procedure Term to find first term */

while ((nextchar='+') or(nextchar='-')) do

begin

nextchar := getchar; /* Skip operator */

Term;

end

end